The international exhibition, held in Philadelphia in 1926, commemorated the 150th anniversary of the signing of the United States Declaration of Independence and the 50th anniversary of the World’s Fair. The concept of holding it started in 1916 and sparked heated debate among citizens, government officials and business owners. Preparations for the large-scale event were hampered by World War I, the flu epidemic and the prohibition of alcohol consumption. The exhibition was still held, although it wasn’t a success. We will tell you more about what happened. Read more at philadelphiaski.com.

International Exposition of Philadelphia: to be or not to be?

In 1916, it was John Wanamaker who came up with the idea to host another international exhibition in the United States. He was an entrepreneur who in his younger years had served on the Finance Committee of the 1876 World’s Fair. At the time, Philadelphia was rapidly developing, so he thought it would be a great venue for such a large-scale event.

Wanamaker obtained the support of the city’s Chamber of Commerce president, who formed a committee to organize and prepare for the event. The Fairmount Parkway was chosen as the location for the future display. However, the United States soon entered the First World War, and the planning process was halted. Subsequently, the flu epidemic began, prohibition was enacted and, by 1920, everyone had forgotten about the exhibition, except for its ideological inspirer.

John Wanamaker continued his press campaign to promote the event. He eventually reassured the city’s new Mayor, Joseph Moore, of its significance, so he established a new committee and association to plan the exhibition. However, disputes immediately arose within this organization regarding the overall vision for the event:

- the mayor and his supporters saw the exhibition as an opportunity for business development, fundraising, tourists and potential partners

- another group, led by local magazine editor Edward Bok, believed that the event should introduce visitors to Philadelphia, its history and its culture.

In 1922, Bok suggested paying $50,000 per year for the job of the fair’s Director General and offered the position to then-Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover. The latter advised the event organizers to prioritize an ideological rather than commercial purpose but declined the position.

Furthermore, financing for the display proved challenging. The budget was repeatedly reduced. The attempt to sell shares to residents failed. Residents of Philadelphia were concerned about the development’s chosen location, as well as the possibility of price increases and greater labor market competition. Church leaders warned of potential criminal activity accompanying the event.

Eventually, it all led to the establishment of the Anti-Sesquicentennial League. It was joined by Joseph Moore, who retired in 1922 but never forgot his clashes with Edward Bok.

In 1924, W. Freeland Kendrick took over as mayor of the city. He oversaw the exhibition’s planning process, which had previously nearly come to an end. The mayor relocated the event to the city’s yet undeveloped southern part. The swampy terrain was drained and filled up, and construction on the main structures began in 1925. The chief architect was Louis Kahn.

Opening and running of the exhibition

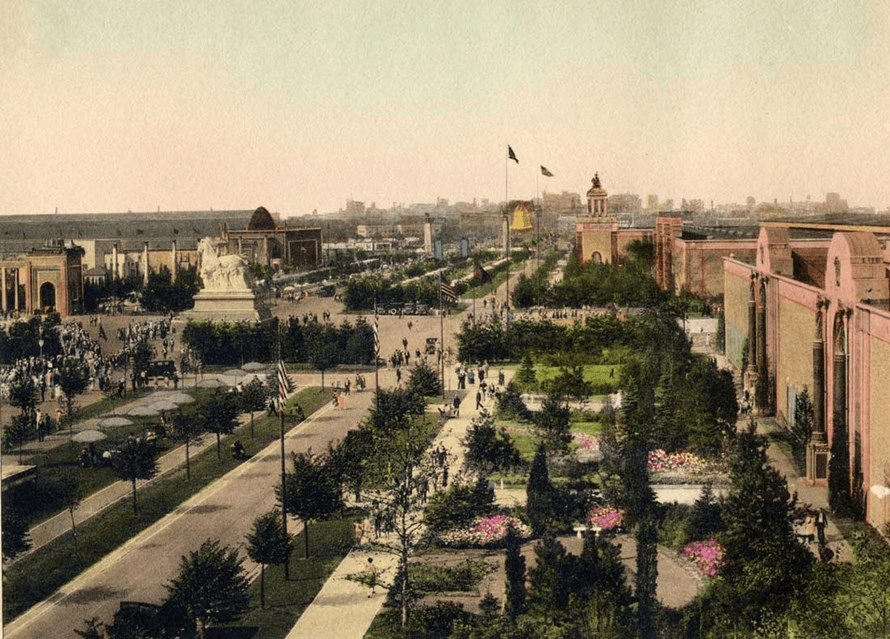

The exhibition’s grand opening took place on May 31, 1926. It ran until late November in South Philadelphia, between 10th and 23rd streets. The opening ceremony was attended by the mayor of the city, Secretary of State Frank Kellogg and Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover. Despite the fact that the exhibition was officially opened, individual buildings were completed only by the end of July.

Five large exhibition halls were built, the city’s colonial High Street was recreated and a 710-by-1,020-foot horseshoe-shaped stadium (which existed until 1992) was constructed, where a championship fight between Gene Tunney and Jack Dempsey was held in September in front of 125,000 spectators. Pavilions for representatives of other states and countries were located on the territory, as well as an emergency hospital, a fire station and a mail service.

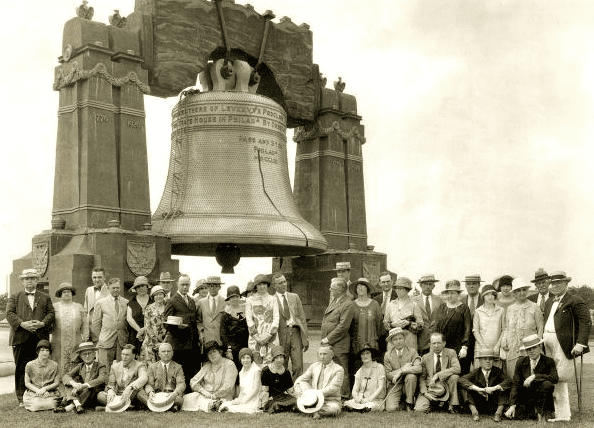

Visitors were greeted at the entry by an eighty-foot replica of the Liberty Bell, which was lit up with 26,000 bulbs. The exposition halls were lit with mechanical lights. The stadium’s powerful lighting, which allowed for use even at night, was revolutionary at the time.

Failure of the event

The organizers expected at least 30 million people to attend the event. However, the actual figure barely exceeded 6 million, and far fewer people paid for entrance. Since the end of June, the exhibition had been open on Sundays, although this did not improve the situation much.

Why did this happen? Possible explanations include ongoing issues over event planning, opposition anti-advertising and bad weather. It rained throughout the majority of the exhibition’s period of operation. Heavy rain even fell on the opening day. Regardless, after the Philadelphia exhibition closed, it was estimated that the event resulted in $5.8 million in debt. It was compensated until 1929.

Despite the failure that took place a century ago, in 2015, the Philadelphia City Council received a proposal to hold a similar exhibition once again. The issue was then taken into consideration, and a new large-scale event will be waiting for Philadelphia residents and visitors in 2026.