David Rittenhouse was a renowned inventor and astronomer, mathematician and clockmaker, surveyor and public official. For many years, he was a member of the American Philosophical Society, rising through its ranks from curator to president. In addition, Rittenhouse became the first director of the United States Mint. Remarkably, he was self-taught, independently acquiring all the knowledge that he would later put into practice. Learn more about this distinguished scientist at philadelphiaski.

A Natural Genius

David was born on April 8, 1732, near Philadelphia. He inherited his first books and carpentry tools from his uncle. From a young age, David demonstrated a high level of intellect, single-handedly building a small working model of his great-grandfather’s paper mill. He went on to create other similar models.

David was not formally schooled, instead educating himself using his family’s library. He was most interested in the natural sciences and mathematics. By age 13, he had mastered Newton’s laws on his own, and at 17, he crafted a clock with wooden gears.

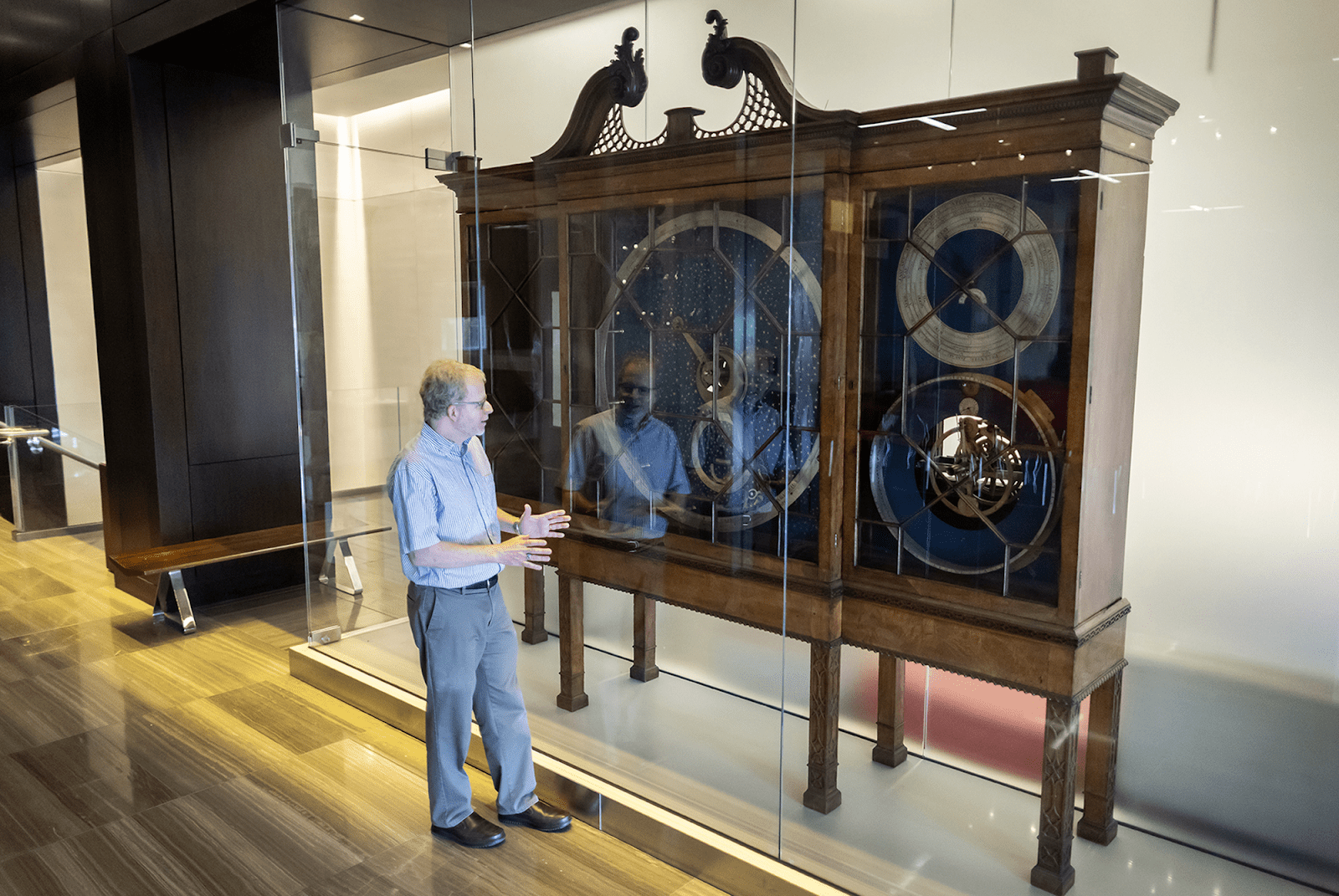

At 19, David opened his own instrument-making workshop on his father’s farm. During this time, he also became interested in astronomy and constructed two orreries (mechanical models of the solar system). The first was gifted to the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University), and the second to the College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania). Interestingly, both have survived into the 21st century and can still be seen at these institutions. They demonstrate solar and lunar eclipses, as well as other astronomical phenomena.

In 1770, David moved to Philadelphia, where he worked as the city surveyor. He used his own terrestrial and astronomical observations to survey rivers and canals and to establish state boundaries.

Science and Practice

David Rittenhouse’s intellect and practical research made him famous not only in the United States but also in Europe. The scientist built his own observatory on his father’s farm, where he made numerous observations and meticulously recorded them. He later published important papers on astronomy; for example, in one article, he explained a possible method for determining Earth’s position in its orbit.

In 1768, Rittenhouse joined the American Philosophical Society. It is worth noting that within this organization, he served as curator, librarian, secretary, vice president, and, from 1791 to 1796, as its president.

He drew significant attention to himself when he announced he would observe the transit of Venus across the Sun. The American Philosophical Society managed to persuade the government to allocate 100 pounds sterling to purchase new telescopes. Society members voluntarily helped equip the observation stations.

This major astronomical event took place on June 3, 1769. Rittenhouse was reportedly so overwhelmed by the sight that he fainted during the observation, but he quickly recovered and continued his work. His results were published in the American Philosophical Society’s Transactions. The scientist used this observation to calculate the distance from the Earth to the Sun as 93 million miles. This result was acclaimed by European scientists.

In addition to his astronomical research, David was involved in mathematics. In 1792, he published a paper describing methods for determining the period of a pendulum. His interests also included magnetism and electricity.

At the University of Pennsylvania, he was a professor of astronomy from 1779 to 1782 and served as vice-provost twice. He was also a member of the university’s board of trustees.

The scientist’s research had a practical dimension. During the American Revolution, he served as an engineer for the Committee of Safety. Under his supervision, cannons were cast, rifles were improved, ammunition was supplied, and sites for powder mills were selected.

Furthermore, Rittenhouse combined his scientific experiments with public service. Specifically:

- In the late 1770s, he was a member of the Pennsylvania Assembly, the Constitutional Convention, and the Board of War.

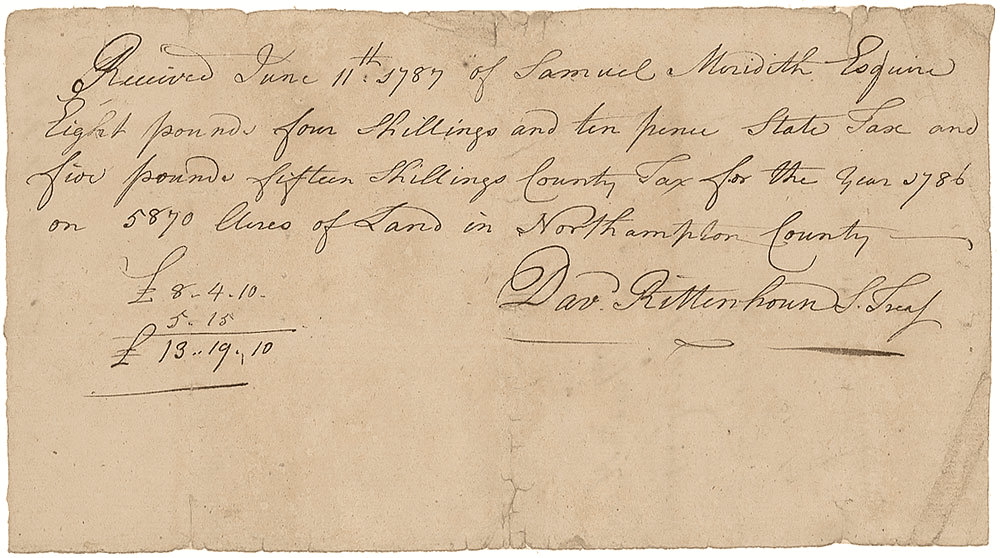

- From 1779 to 1787, he was the State Treasurer.

- From 1792 to 1795, he served as the Director of the U.S. Mint.

Thus, his scientific and public life was both busy and highly productive in all spheres. David never lost his sincere curiosity about the world and sought to improve it in every way he could.

Personal Life

The distinguished scientist married twice. His first wife was Eleanor Coulston, whom he married in 1766. In this marriage, two daughters were born, Elizabeth and Esther. The latter later named her son in honor of her father.

In 1770, Eleanor Rittenhouse became pregnant for a third time, but the birth ended in tragedy: both mother and child died. This occurred on February 23, 1771. David’s wife was only 35 years old.

In late 1772, he married for a second time. His new wife was Hannah Jacobs. They lived together until David’s life ended on June 26, 1796. His wife outlived him by three years.